A biweekly newsletter with public space news, resources, and opportunities.

A curated dispatch on all things public markets plus the latest announcements from the Market Cities Program.

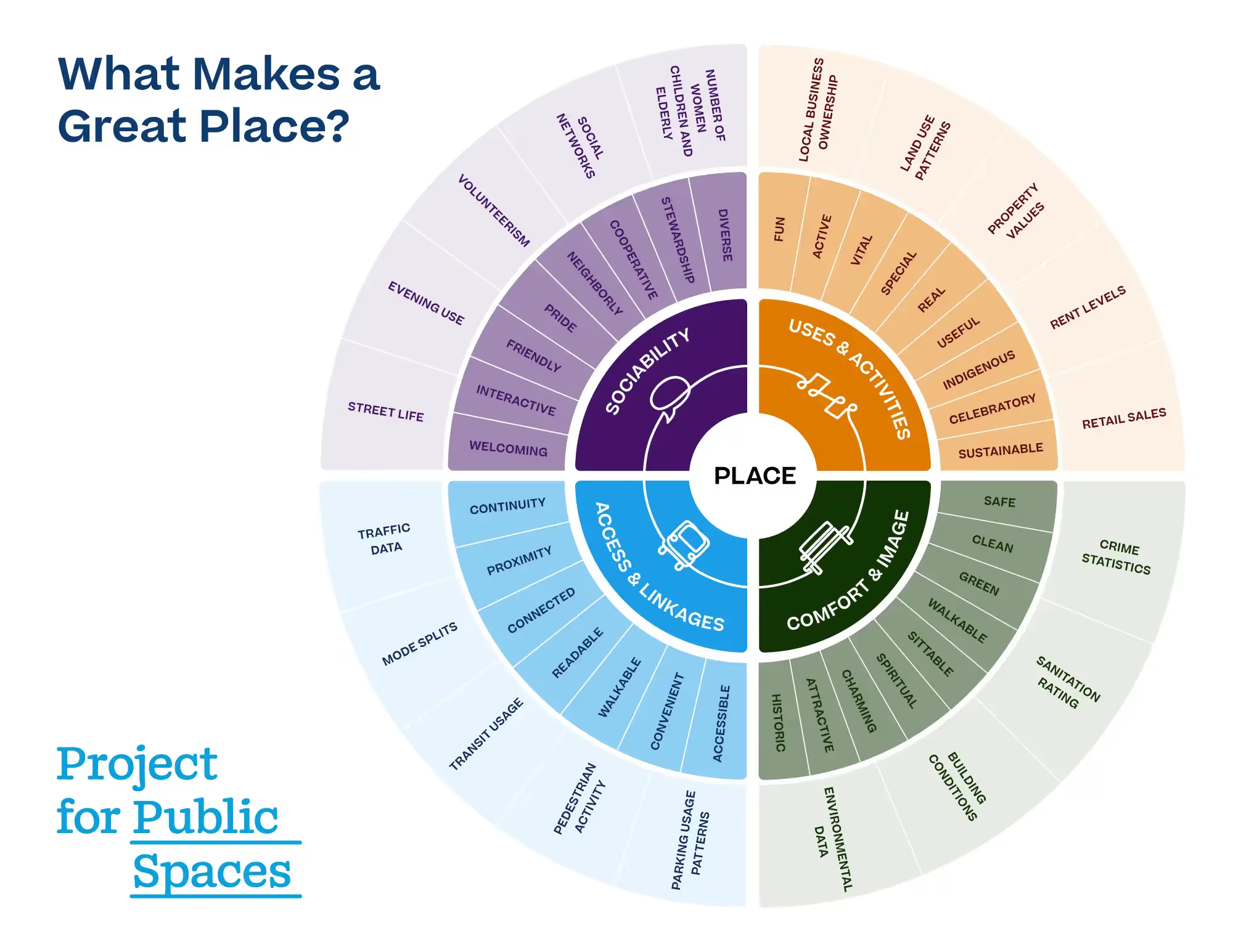

As both an overarching idea and a hands-on approach for improving a neighborhood, city, or region, placemaking inspires people to collectively reimagine and reinvent public spaces as the heart of every community. Strengthening the connection between people and the places they share, placemaking refers to a collaborative process by which we can shape our public realm in order to maximize shared value. More than just promoting better urban design, placemaking facilitates creative patterns of use, paying particular attention to the physical, cultural, and social identities that define a place and support its ongoing evolution.

With community-based participation at its center, an effective placemaking process capitalizes on a local community's assets, inspiration, and potential, and it results in the creation of quality public spaces that contribute to people's health, happiness, and well being.

When Project for Public Spaces surveyed people about what placemaking means to them, we found that it is a crucial and deeply-valued process for those who feel intimately connected to the places in their lives. Placemaking shows people just how powerful their collective vision can be. It helps them to re-imagine everyday spaces, and to see anew the potential of parks, downtowns, waterfronts, plazas, neighborhoods, streets, markets, campuses and public buildings.

Placemaking is not a new idea. Although Project for Public Spaces began consistently using the term "placemaking" in the mid-1990s to describe our approach, some of the thinking behind Placemaking gained traction in the 1960s, when our mentors like Jane Jacobs and William H. Whyte introduced groundbreaking ideas about designing cities for people, not just cars and shopping centers. Their work focuses on the social and cultural importance of lively neighborhoods and inviting public spaces: Jacobs encouraged everyday citizens to take ownership of streets through the now-famous idea of “eyes on the street,” while Holly Whyte outlined key elements for creating vibrant social life in public spaces. Applying the wisdom of these (and other) urban pioneers, since 1975 Project for Public Spaces has gradually developed a comprehensive Placemaking approach.

Throughout our experience working with over 3,500 communities—in all 50 U.S. states and in over 50 countries—Project for Public Spaces continues to show by example how adopting a collaborative community process is the most effective approach for creating and revitalizing public spaces. For us, placemaking is both a process and a philosophy. It is centered around observing, listening to, and asking questions of the people who live, work, and play in a particular space in order to understand their needs and aspirations for that space and for their community as a whole. With this knowledge, we can come together to create a common vision for that place. The vision can evolve quickly into an implementation strategy, beginning with small-scale "Lighter, Quicker, Cheaper" improvements that bring immediate benefits both to the spaces themselves and the people who use them.

Unfortunately, the rigid planning processes of the 20th century have become so institutionalized that community stakeholders rarely have the chance to voice their own ideas and aspirations about the places they inhabit. Placemaking can break down these silos by showing planners, designers, and engineers the broad value of moving beyond the narrow focus of their own professions, disciplines, agendas. Experience has shown us that when developers and planners welcome this kind of grassroots involvement, they spare themselves a lot of headaches. Common problems like traffic-dominated streets, little-used parks, and isolated or underperforming development projects can be addressed—or altogether avoided—by embracing a model of placemaking that views a place in its entirety, rather than zeroing in on isolated components.

The Project for Public Spaces placemaking approach can be a springboard for community revitalization. Emerging from forty years of practice, our 11 Principles of Placemaking offer guidelines to help communities (1) integrate diverse opinions into a cohesive vision, (2) translate that vision into a plan and program of uses, and (3) ensure the sustainable implementation of the plan. Turning a shared vision into a reality–into a truly great place–means finding the patience to take small steps, to truly listen, and to see what works best in a particular context.

Just as community input is essential to the placemaking process, it is equally important to have a mutual understanding of the ways in which great places foster successful social networks and benefit multiple stakeholders and initiatives at once. The 11 Principles, along with and other tools we’ve developed for improving places (such as the Power of 10), have helped citizens bring immense changes to their communities–changes that are often far more extensive than the original vision had imagined.

Placemaking is at the heart of Project for Public Spaces’s work and mission, but we do not trademark it as our property. It belongs to anyone and everyone who is sincere about creating great places, and who understands how a strong sense of place can influence the physical, social, emotional, and ecological health of individuals and communities everywhere. We do feel a responsibility to continue protecting, practicing, and advocating for the community-driven, bottom-up approach that placemaking describes. To be successful, this process requires great leadership and action on all levels. Leaders need not, and certainly should not, have all the answers, and by acknowledging this, and providing space for experimentation and collaboration, Placemaking allows an even bolder process to unfold.

Today, the term "placemaking" is used in many settings–not just by citizens and organizations committed to grassroots community improvement, but also by planners and developers who use it as a “brand” to imply authenticity and quality, even if their projects don’t always live up to that promise. But using “placemaking” in reference to a process that isn't really rooted in public participation dilutes its potential value. Making a place is not the same as constructing a building, designing a plaza, or developing a commercial zone. As more communities engage in placemaking and more professionals come to call their work “placemaking,” it is important to preserve the meaning and integrity of the process. A great public space cannot be measured by its physical attributes alone; it must also serve people as a vital community resource in which function always trumps form. When people of all ages, abilities, and socio-economic backgrounds can not only access and enjoy a place, but also play a key role in its identity, creation, and maintenance, that is when we see genuine placemaking in action.

Placemaking pays close attention to the myriad ways in which the physical, social, ecological, cultural, and even spiritual qualities of a place are intimately intertwined, and we continue to be inspired by the visionary placemakers who have worked to promote this vision for generations.

Placemaking belongs to everyone: its message and mission is bigger than any one person or organization. As a "backbone organization," Project for Public Spaces remains dedicated to supporting the movement, growing the network, and sharing our experience and resources with placemakers and allies everywhere.

Placemaking is

Placemaking is not

Citation (MLA 8): “What Is Placemaking?” Project for Public Spaces, 2007, https://www.pps.org/article/what-is-placemaking

The rich text element allows you to create and format headings, paragraphs, blockquotes, images, and video all in one place instead of having to add and format them individually. Just double-click and easily create content.

The rich text element allows you to create and format headings, paragraphs, blockquotes, images, and video all in one place instead of having to add and format them individually. Just double-click and easily create content.

Body Text Body Link

The rich text element allows you to create and format headings, paragraphs, blockquotes, images, and video all in one place instead of having to add and format them individually. Just double-click and easily create content.

Here is some highlighted text from the article.

Headings, paragraphs, blockquotes, figures, images, and figure captions can all be styled after a class is added to the rich text element using the "When inside of" nested selector system.

Headings, paragraphs, blockquotes, figures, images, and figure captions can all be styled after a class is added to the rich text element using the "When inside of" nested selector system.

Headings, paragraphs, blockquotes, figures, images, and figure captions can all be styled after a class is added to the rich text element using the "When inside of" nested selector system.

We are committed to access to quality content that advances the placemaking cause—and your support makes that possible. If this article informed, inspired, or helped you, please consider making a quick donation. Every contribution helps!

Project for Public Spaces is a 501(c)(3) tax-exempt organization and your donation is tax-deductible within the guidelines of U.S. law.